Vermont’s forests are home to a fascinating variety of woodpeckers, each with unique colors, calls, and behaviors. These birds play a crucial role in forest ecosystems by controlling insects and creating nesting cavities for other species.

From the tiny Downy Woodpecker to the impressive Pileated Woodpecker, Vermont offers opportunities to observe these skilled climbers at work. Their drumming sounds and distinctive markings make them easier to identify in the dense woodlands.

Learning to recognize the different woodpecker species enhances outdoor adventures, whether hiking, birdwatching in backyards, or exploring parks. This guide covers 9 woodpeckers in Vermont, complete with pictures and identification tips.

Types of Woodpeckers Found in Vermont

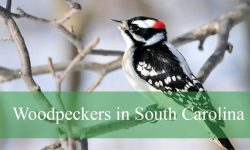

Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens)

The Downy Woodpecker is Vermont’s smallest woodpecker, measuring about 6–7 inches in length with a wingspan of roughly 10–12 inches. It has a compact body, short bill, and a distinctive black-and-white patterned head. Males feature a small red patch on the back of the head, while females lack this mark. Its black-and-white striped back and white underside make it easily distinguishable from other similar species.

Downy Woodpeckers are highly agile and can cling to thin branches and twigs with ease. They forage primarily on tree trunks, branches, and shrubs, using their small bills to peck and probe for insects. They also eat seeds and occasionally berries, especially during the winter when insects are scarce. Unlike larger woodpeckers, their light frame allows them to search for food on delicate limbs without breaking them.

These birds are generally non-migratory in Vermont, remaining in forests, woodlots, and suburban areas year-round. They nest in cavities excavated in dead or decaying trees, sometimes reusing abandoned holes. The female lays 3–8 white eggs, which both parents incubate for about 12 days. The young fledge approximately 20–25 days after hatching, often staying nearby for a few more weeks.

Downy Woodpeckers communicate with sharp “pik” calls and drum rapidly on thin branches or metal surfaces. Their drumming serves as a territorial display and a way to attract mates during the breeding season. These woodpeckers play a vital ecological role in Vermont by controlling insect populations and creating nesting cavities used by other bird species.

Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides villosus)

The Hairy Woodpecker is a medium-sized woodpecker, slightly larger than the Downy, measuring 9–10 inches long with a wingspan of 16–18 inches. It closely resembles the Downy Woodpecker but has a longer, more robust bill and lacks the small black spots on the white outer tail feathers. Its black-and-white coloration includes a black back with a white stripe down the center, white underparts, and males display a small red patch on the back of the head.

Hairy Woodpeckers forage mostly on larger trees, using their powerful bills to excavate wood in search of insects, particularly beetle larvae and ants. They occasionally feed on sap and berries but are primarily insectivorous. Their strong flight and deliberate pecking movements distinguish them from the smaller, more nimble Downy Woodpecker.

In Vermont, Hairy Woodpeckers inhabit mature deciduous and mixed forests, as well as wooded suburban areas. They excavate nest cavities in dead or dying trees, often at heights of 10–60 feet above the ground. The female lays 3–7 white eggs, and both parents share incubation duties. Chicks fledge after roughly 24–28 days but continue to be fed by parents for a short period afterward.

Hairy Woodpeckers drum steadily on tree trunks or snags to establish territory and attract mates. Their drumming is slower and more resonant than that of Downy Woodpeckers due to their larger size. These woodpeckers also contribute to forest health by controlling insect populations and creating cavities that benefit secondary cavity-nesters like chickadees and nuthatches.

Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus)

The Northern Flicker is a large woodpecker species, measuring 11–12 inches long with a wingspan of 16–20 inches. Unlike most woodpeckers, it often forages on the ground. It has a brown body with black bars on the back and wings, a spotted chest, a black bib, and a white rump visible in flight. In Vermont, the Yellow-shafted Flicker is most common, with bright yellow underwing and tail feathers. Males have a red crescent on the nape and a black malar stripe along the cheek.

Northern Flickers primarily feed on ants and beetles, often probing the soil with their long bills. They also eat seeds and berries, occasionally visiting bird feeders. Unlike other woodpeckers, they forage extensively on lawns, fields, and forest edges, using their sticky tongues to capture insects underground. Their behavior includes distinctive “flickering” wing displays and loud, rolling calls.

These woodpeckers nest in tree cavities, often in dead or decaying trees, and sometimes in wooden fence posts or utility poles. The female lays 5–8 eggs, which both parents incubate for approximately 12 days. Chicks fledge around 24 days after hatching, with both parents feeding the young during this period. Northern Flickers are migratory in Vermont, often spending winters in the southern United States.

Northern Flickers drum and call loudly to establish territories, and their drumming can be heard for long distances. Their ecological role is significant, as they control ground-dwelling insects and provide nesting cavities for secondary cavity-nesting birds. They are also a favorite among birdwatchers due to their striking plumage and ground-foraging behavior.

Red-bellied Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus)

The Red-bellied Woodpecker is a medium-sized woodpecker, 9–10 inches long with a wingspan of 16–18 inches. Its most notable feature is a bright red cap extending from the bill to the nape, though the “red belly” is often faint. The back and wings are black with white bars, and the underparts are pale with light streaking. Males have a more extensive red on the head compared to females, making them easier to identify.

These woodpeckers are highly versatile in feeding, consuming insects, fruits, nuts, and occasionally bird eggs or nestlings. They forage on tree trunks, branches, and sometimes on the ground, using their strong bills to excavate bark and search for hidden insects. In winter, they may visit backyard feeders for suet, sunflower seeds, and peanuts.

Red-bellied Woodpeckers in Vermont prefer mixed forests, wooded suburbs, and parks with mature trees. They excavate nesting cavities in dead or dying trees, usually high above the ground. The female lays 3–6 eggs, and both parents incubate them for about 12 days. Fledging occurs roughly 25–30 days after hatching, with parental care continuing for several weeks.

These woodpeckers are vocal and frequently drum on trees or metal surfaces to communicate and defend their territory. Their loud rolling calls are characteristic of the species. By controlling insect populations and creating cavities, they play an essential ecological role in Vermont’s forested environments, benefiting many other birds and small animals.

Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus)

The Pileated Woodpecker is Vermont’s largest woodpecker, measuring 16–19 inches long with a wingspan of 26–30 inches. It is striking with a predominantly black body, white stripes on the face and neck, and a bright red crest. Males have a red mustache stripe, while females’ mustaches are black. Its powerful bill is chisel-like, enabling it to excavate large holes in trees to access insects.

These woodpeckers primarily feed on carpenter ants, beetle larvae, and other insects, but also consume fruits and nuts seasonally. They excavate massive rectangular holes in dead or decaying trees, creating feeding sites and nesting cavities. Their foraging behavior leaves noticeable holes and wood chips, which are a hallmark of their presence.

Pileated Woodpeckers inhabit mature deciduous and mixed forests in Vermont, especially areas with abundant dead trees. They nest in large tree cavities, laying 3–5 white eggs. Both parents incubate the eggs for about 15–18 days, and the chicks fledge roughly 28–30 days after hatching. These woodpeckers are largely non-migratory, staying in their territories year-round.

Their deep, resonant drumming is used for communication and territory defense, and their loud, ringing calls are often heard before the bird is seen. By excavating large cavities, Pileated Woodpeckers support other cavity-nesting species and contribute to forest ecosystem health, making them one of Vermont’s most iconic birds.

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius)

The Yellow-bellied Sapsucker is a medium-sized woodpecker, measuring 7.5–9 inches in length with a wingspan of 14–17 inches. It has a striking black-and-white patterned face with a red forehead, throat, and crown in males, while females have a less intense red throat. Its back is barred with black and white, and the belly shows a subtle yellow wash that gives the bird its name.

This species feeds primarily by drilling rows of small holes, or “sap wells,” in the bark of trees to access sap and the insects attracted to it. They also consume berries and fruits, particularly in the fall. Unlike other woodpeckers, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers often move in flocks during migration, tapping multiple trees to establish feeding territories.

In Vermont, they inhabit mixed woodlands, especially those with abundant maples, birches, and aspens, which provide ideal sap sources. Nesting occurs in tree cavities, often in dead or decaying trees. Females lay 4–7 eggs, and both parents incubate for about 12 days. Chicks fledge roughly 24 days after hatching and are fed by parents until they can forage independently.

Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers are migratory, spending winters in the southeastern U.S., Central America, and the Caribbean. Their drumming and sharp “wick-wick” calls help maintain territories and communicate with mates. They play an important ecological role by providing sap for other birds and mammals and controlling tree-boring insect populations.

Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus)

The Red-headed Woodpecker is a medium-sized bird, 7.5–9 inches long with a wingspan of 16–19 inches. Its most striking feature is the completely red head and neck, contrasting sharply with a white body and black back and wings. Both sexes share the same coloration, making identification easy from a distance.

These woodpeckers are omnivorous, feeding on insects, fruits, nuts, seeds, and occasionally small vertebrates. They are known for caching food in tree crevices for later consumption. Their foraging behavior is versatile—they glean insects from branches, catch flying insects mid-air, and even feed on the ground.

Red-headed Woodpeckers prefer open woodlands, orchards, and forest edges in Vermont. They excavate nest cavities in dead trees or utility poles, laying 3–7 eggs. Both parents participate in incubation for about 13–14 days. Chicks fledge approximately 26–28 days after hatching and continue to receive parental care briefly.

This species is highly vocal, using a variety of harsh calls and drumming to defend territories. Red-headed Woodpeckers are declining in some areas due to habitat loss, but in Vermont, they remain a striking sight for birdwatchers. Their cavity excavation provides nesting opportunities for other birds and small mammals, supporting forest biodiversity.

Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus)

The Black-backed Woodpecker is a rare woodpecker in Vermont, measuring 9–10 inches long with a wingspan of 16–18 inches. It has an entirely black back, pale underparts, and a yellow patch on the crown of males. Females lack the yellow crown but share the same body coloration. Its bill is long and chisel-like, suited for excavating beetle larvae from burned or dead trees.

This species specializes in feeding on wood-boring beetles, especially in recently burned forests or areas affected by beetle outbreaks. They use their strong bills to peck and probe the bark, often clinging to vertical trunks for long periods. Their diet may also include other insects and occasionally seeds.

Black-backed Woodpeckers inhabit coniferous forests and areas with recent fire activity, which provides abundant food sources. They excavate nest cavities in dead trees and snags, laying 3–7 eggs per clutch. Both parents share incubation, which lasts around 12–14 days, and the chicks fledge after 24–28 days.

Vocalizations include sharp “kik” calls and drumming on dead trees. By specializing in beetle infestations, Black-backed Woodpeckers contribute to forest health and nutrient cycling. Although rare in Vermont, they are a critical species for monitoring forest ecosystem conditions.

American Three-toed Woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis)

The American Three-toed Woodpecker is uncommon in Vermont, measuring 8–9 inches in length with a wingspan of 14–17 inches. It has a mostly black-and-white barred back, pale underparts, and a yellow crown on males. Its three-toed feet distinguish it from most woodpeckers, which have four toes, providing a specialized grip on tree trunks.

This woodpecker feeds primarily on insects, especially bark beetles and larvae, by excavating the bark of dead or dying conifers. They also consume seeds when insects are scarce. Foraging is usually slow and methodical, with birds clinging vertically to trunks for long periods as they search for prey.

In Vermont, they inhabit mature coniferous forests and areas affected by fire or beetle outbreaks. Nesting occurs in cavities excavated in dead trees, with 3–6 eggs per clutch. Both parents incubate for about 12 days, and chicks fledge around 22–25 days after hatching.

Their drumming is deliberate and resonant, used for communication and territory defense. As a specialized insectivore, the American Three-toed Woodpecker plays an important role in controlling bark beetle populations, helping to maintain healthy forest ecosystems. Their rarity in Vermont makes sightings highly valued among birdwatchers.

FAQs About Woodpeckers in Vermont

What woodpecker species are most common in Vermont?

The most common woodpeckers in Vermont include the Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, Red-bellied Woodpecker, and Pileated Woodpecker. These species are frequently found in forests, woodlots, and suburban areas throughout the state.

How can I tell a Downy Woodpecker apart from a Hairy Woodpecker?

Downy Woodpeckers are smaller, about 6–7 inches long, with a short, delicate bill and black spots on their outer tail feathers. Hairy Woodpeckers are larger, 9–10 inches long, with a longer, more robust bill and unspotted tail feathers. Size and bill length are the easiest distinguishing features.

When do Vermont woodpeckers breed?

Most woodpeckers in Vermont begin breeding in late spring, typically from April to June. They excavate cavities in dead or decaying trees, where females lay 3–8 eggs depending on the species. Both parents usually participate in incubation and feeding of the chicks.

What do Vermont woodpeckers eat?

Woodpeckers primarily feed on insects, larvae, and ants found in or under tree bark. Some species, like the Red-bellied and Red-headed Woodpeckers, also consume fruits, nuts, seeds, and occasionally small vertebrates. Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers specialize in tree sap and the insects attracted to it.

Where can I see woodpeckers in Vermont?

Woodpeckers are most commonly observed in mature deciduous or mixed forests, woodlots, and parks. Northern Flickers are often seen foraging on the ground, while species like the Pileated Woodpecker prefer large, standing dead trees for feeding and nesting.

Are any Vermont woodpeckers migratory?

Yes. Some species, such as the Northern Flicker and Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, migrate south during winter. Others, including Downy, Hairy, Red-bellied, and Pileated Woodpeckers, generally remain in Vermont year-round.

Why do woodpeckers drum on trees?

Drumming is a primary method for communication and territory establishment. It signals presence to potential mates and warns other birds to stay away. Different species produce distinct drumming patterns, which can help identify them even without visual contact.

Are any Vermont woodpeckers rare or declining?

Yes. The Black-backed Woodpecker and American Three-toed Woodpecker are rare in Vermont. Habitat loss and changes in forest composition can impact their populations. Conservation of mature forests and dead trees is essential for supporting these species.

Can woodpeckers damage trees or property?

Woodpeckers primarily excavate dead or dying trees, which is beneficial for forest health. Occasionally, they may peck at wooden siding, utility poles, or houses while searching for insects or sap. Using deterrents like reflective tape, netting, or noise devices can help reduce property damage.