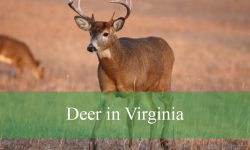

Deer are an iconic part of Pennsylvania’s wildlife heritage, deeply woven into the natural landscape and the cultural traditions of the state. From forested mountains to rural farmlands, these graceful animals are a common and admired sight. Whether you’re a hunter, a nature enthusiast, or someone who simply enjoys spotting wildlife, Pennsylvania offers unique opportunities to observe and appreciate these fascinating creatures in their natural habitat.

While the White-tailed Deer is by far the most abundant and familiar species, Pennsylvania is also home to other members of the deer family that deserve attention. A small but thriving elk population lives in the north-central region, offering an entirely different deer-watching experience. Additionally, some rare or introduced deer species occasionally appear in the state, making Pennsylvania’s deer diversity more interesting than many realize.

In this article, we’ll explore four types of deer in Pennsylvania, complete with pictures and identification tips. From the native white-tailed deer to the majestic elk and rare exotic sightings, you’ll discover how to recognize each species, where they live, and what makes them unique in the Keystone State.

Different Types of Deer in Pennsylvania

White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus)

The White-tailed Deer is Pennsylvania’s most abundant large mammal and a symbol of the state’s forests. Adults typically stand 3 to 3.5 feet at the shoulder, with males weighing between 150 to 300 pounds and females ranging from 90 to 150 pounds. Their sleek, reddish coats in summer help them blend into lush vegetation, while their duller, grayish winter coats offer camouflage against bare trees and snow. Their most recognizable trait is the bright white underside of the tail, which they raise like a flag to signal danger as they flee.

These deer have adapted exceptionally well to Pennsylvania’s diverse landscapes. You can find them in dense hardwood forests, open meadows, farm fields, and even near residential neighborhoods. They are highly mobile and adjust their ranges based on food availability, cover, and seasonal changes. They feed on a broad diet that includes acorns, berries, twigs, grass, corn, and ornamental plants—making them a common visitor in suburban gardens.

White-tailed Deer are mostly active at dawn and dusk, a behavior known as crepuscular activity. During the fall rutting season (October to early December), bucks become more visible as they seek out does, spar with rivals, and patrol their territory. In spring, does give birth to one or two fawns, often leaving them hidden in tall grass or underbrush while they forage, relying on the fawns’ spotted coats and lack of scent for protection from predators.

This species is present in all 67 counties and is a cornerstone of the state’s hunting culture and wildlife management programs. Top spots to see White-tailed Deer include Rothrock State Forest, Michaux State Forest, and Valley Forge National Historical Park, especially during early morning or late afternoon hours. The Pennsylvania Game Commission conducts regular population assessments and harvests to maintain ecological balance and reduce conflicts with humans.

Elk (Cervus canadensis)

Elk are majestic and much larger than White-tailed Deer, making them an awe-inspiring sight for Pennsylvania wildlife enthusiasts. Adult bulls can weigh over 900 pounds and stand up to 5 feet at the shoulder, while cows are slightly smaller, averaging around 600 pounds. They have a tan-colored body with a distinctive dark brown mane and pale rump patch. Males grow massive, branching antlers each year that can reach lengths over four feet, which they shed during winter and regrow in spring.

Historically, elk were native to Pennsylvania but were eliminated by the late 1800s due to overhunting and habitat destruction. In the early 1900s, the Pennsylvania Game Commission reintroduced elk from Yellowstone and other states. These efforts were successful, and today, a wild population of around 1,400 elk roams free in the north-central part of the state. Elk now inhabit parts of Elk, Cameron, Clinton, Potter, Clearfield, and Centre counties where reclaimed strip mines, meadows, and second-growth forests offer ample grazing space.

Elk are herd animals that prefer open meadows and forest edges. They graze mostly on grasses, forbs, and shrubs, and tend to be most active at dawn and dusk. In the fall, the breeding season known as the “rut” brings dramatic changes in their behavior. Bulls can be seen bugling—a loud, high-pitched call—to attract females and challenge rivals. Their sparring and bugling attract thousands of visitors each year to public viewing areas, especially around Benezette, which has become the epicenter of elk tourism in Pennsylvania.

Thanks to careful habitat management and regulated hunting seasons, elk have become one of the state’s greatest conservation success stories. Viewing platforms, visitor centers, and guided tours now offer safe and sustainable ways for people to admire these incredible animals up close. The Pennsylvania Elk Country Visitor Center is one of the best places to learn about and observe the herd year-round.

Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus)

Mule Deer are native to the western United States and are not part of Pennsylvania’s natural fauna. They are named for their unusually large, mule-like ears which constantly rotate to detect sounds. Mule Deer have a light brown to grayish coat and a distinctive black-tipped tail, unlike the broader white tail of the White-tailed Deer. Bucks also have forked antlers, in contrast to the single main beam with tines seen in White-tailed Deer.

Because Pennsylvania lies far outside the natural range of Mule Deer, these animals are not found in the wild within the state. Their preferred habitats include dry deserts, foothills, rocky slopes, and high plains—landscapes that are far more common in states like Colorado, Utah, or New Mexico. They are adapted to more arid conditions and are less likely to thrive in the humid, forested environments typical of the eastern U.S.

That said, Mule Deer might occasionally be seen in captivity, on private game preserves, or exotic wildlife ranches in Pennsylvania. Escaped individuals are extremely rare and are not known to form wild, sustainable populations anywhere in the state. If spotted, they are generally considered outliers or escapees from human-controlled environments.

Due to the absence of suitable ecological conditions and the strong presence of White-tailed Deer, the establishment of Mule Deer in Pennsylvania is unlikely. Wildlife officials do not include this species in conservation or management plans, and sightings should be reported as potential non-native occurrences.

Sika Deer (Cervus nippon)

Sika Deer are an exotic species originally native to East Asia, including Japan, Taiwan, and parts of China and Korea. They are noticeably smaller than White-tailed Deer and elk, with adults weighing between 70 and 150 pounds. Their coats are dark brown in winter and reddish with faint white spots in summer, sometimes resembling a small elk in build. One of their most unusual traits is their vocalization—they emit loud whistles and squeals, particularly during the rutting season.

Sika Deer are not naturally found in Pennsylvania’s wildlands but have been introduced into nearby states such as Maryland and Virginia, particularly on the Delmarva Peninsula. These populations are typically descendants of escaped deer from private hunting preserves. While some Sika Deer may escape from similar facilities in Pennsylvania, there is no evidence of self-sustaining wild populations within the state.

Their preferred habitat is very different from that of native deer. Sika Deer thrive in marshes, wetlands, and coastal forests—areas where they can graze on sedges, grasses, and aquatic plants. In regions where they’ve established, they sometimes compete with native deer for food and habitat, raising ecological concerns among biologists.

In Pennsylvania, Sika Deer are extremely rare and, when present, are usually confined to enclosures or ranches. Because of their status as a non-native, introduced species, they are not protected under the same wildlife laws as native deer and are not part of any state-managed conservation efforts. Still, their occasional appearance in private lands adds an exotic twist to the state’s deer diversity, albeit one with limited ecological impact.

When and Where to See and Hunt White-tailed Deer in Pennsylvania

The best time to see White-tailed Deer in Pennsylvania is during the early morning and late evening hours, when these animals are most active. Wildlife watchers often have great success spotting deer during the fall rutting season, which typically peaks in late October through mid-November. During this time, bucks are more visible as they roam widely in search of mates, often moving during daylight hours. In spring and early summer, it’s also common to see does with their fawns in meadows, forest edges, and along trails.

Some of the best places to observe White-tailed Deer include Rothrock State Forest, Michaux State Forest, and Valley Forge National Historical Park, where herds are often seen grazing near clearings or along forest roads. Elk County, though famous for elk, also supports healthy populations of White-tailed Deer. In suburban and rural areas with nearby woodlands, deer are often seen feeding on gardens, shrubs, and field crops.

For hunters, Pennsylvania offers a well-managed and highly popular white-tailed deer hunting season, typically starting with archery in early October and extending through rifle and muzzleloader seasons into December and sometimes January. The general firearms season, which usually begins after Thanksgiving, is the most popular time to hunt, drawing hundreds of thousands of participants each year. During this period, deer are still in their post-rut movement patterns and often appear near feeding areas.

Top hunting regions include Centre, Tioga, Bradford, Clearfield, and Lycoming counties, which offer large tracts of public land, such as state game lands and national forests. The Pennsylvania Game Commission provides maps, hunting zones, and population data to help hunters plan effectively. Whether you’re observing or hunting, success depends heavily on understanding deer movement patterns, seasonal changes, and habitat preferences in the area.