Florida is famous for its sunny beaches, lush forests, and unique wildlife. Amid this natural beauty, the state is also home to a variety of poisonous and venomous animals. From snakes and spiders to marine species, understanding these creatures is essential for anyone exploring the outdoors.

Encounters with these animals are relatively rare, but knowing how to identify them and recognizing their habitats can prevent dangerous situations. Some species, like the Eastern Coral Snake or Black Widow Spider, carry potent venom, while others, such as marine Lionfish, pose risks through stings.

This guide highlights 12 of Florida’s most poisonous wild animals, providing identification tips, habitat information, and safety advice. Hikers, beachgoers, and wildlife enthusiasts can learn how to observe these creatures safely and respectfully.

Types of Poisonous Wild Animals Found in Florida

Eastern Coral Snake (Micrurus fulvius)

The Eastern Coral Snake is one of Florida’s most recognizable venomous snakes, known for its striking red, yellow, and black banded pattern. These bands run the entire length of the snake’s body, making it easy to identify for those familiar with the “red touch yellow, kill a fellow” mnemonic. Adult snakes typically range from 20 to 30 inches long, though some can grow up to 48 inches.

This snake primarily inhabits pine flatwoods, scrublands, and sandy forests across northern and central Florida. It often hides under leaf litter, logs, or loose soil, making encounters rare. Despite their bright coloration, Eastern Coral Snakes are shy and prefer to avoid human contact.

Eastern Coral Snakes are highly venomous, with neurotoxic venom that can cause respiratory failure if untreated. Their fangs are small and located at the front of the mouth, which makes delivering venom less likely unless they bite and hold on. Bites are very rare, but immediate medical attention is essential.

They feed on smaller snakes, lizards, amphibians, and occasionally insects. Breeding occurs in spring, with females laying 3 to 12 eggs in hidden areas. While dangerous, Eastern Coral Snakes play an important role in controlling populations of small reptiles in their habitats.

Southern Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix mokasen)

The Southern Copperhead is a venomous pit viper found in parts of northern and central Florida, often in forested areas, swamps, and near streams. Adults are usually 24 to 36 inches long and are easily recognized by their copper-colored heads and hourglass-shaped dorsal bands.

This species is generally non-aggressive and relies on camouflage to avoid predators. They often freeze when approached, which can lead to accidental encounters. Southern Copperheads are most active during warm months and usually hunt in the early morning or evening.

Copperheads possess hemotoxic venom that affects blood and tissue, causing pain, swelling, and sometimes tissue necrosis. Although their bites are rarely fatal to humans, they can cause significant discomfort and require immediate medical treatment. The snake delivers venom through long, hinged fangs capable of deep penetration.

Their diet includes small mammals, amphibians, and insects. Breeding occurs in late summer, and females give live birth to 3–10 young after a gestation period of about three months. Copperheads are an important part of the ecosystem, controlling rodent populations.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus)

The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake is the largest venomous snake in North America, with adults often exceeding six feet in length. Its distinctive diamond-shaped dorsal patterns, bordered in yellow or white, make it one of the most visually striking snakes in Florida.

This rattlesnake primarily inhabits pine forests, dry scrub, and coastal hammocks throughout northern and central Florida. They often hide in dense vegetation or burrows, using their camouflage to ambush prey. Their signature rattle warns predators and humans of their presence.

Eastern Diamondbacks possess potent hemotoxic venom, capable of causing severe pain, swelling, tissue damage, and even death if untreated. Bites require immediate medical care. The species uses its long, retractable fangs to inject venom deeply, making encounters particularly dangerous.

Their diet consists mainly of small mammals, birds, and occasionally reptiles. Eastern Diamondbacks are solitary except during mating season, which occurs in spring. Female rattlesnakes give birth to live young, usually 7–21 per litter. They are apex predators in their habitats and help maintain balanced populations of small mammals.

Pygmy Rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius)

The Pygmy Rattlesnake is a small, venomous pit viper, rarely exceeding 24 inches in length. It has a gray or brown body with dark, oval dorsal blotches and a short, stubby rattle that produces a buzzing sound when threatened. Despite its small size, its venom is potent and capable of causing significant pain.

This species inhabits wetlands, pine flatwoods, and scrubby areas throughout Florida. It is secretive and often hides under leaf litter, logs, or dense vegetation, making human encounters uncommon. Pygmy Rattlesnakes are active during the day in cooler months and at night during hotter periods.

The venom is hemotoxic, affecting blood and tissue. Bites can result in pain, swelling, and tissue damage, though fatalities are extremely rare due to the small quantity of venom delivered. Medical attention should always be sought after a bite, particularly for children or pets.

Pygmy Rattlesnakes feed on small mammals, amphibians, and lizards. They are solitary except for the mating season, which usually occurs in late spring. Females give birth to live young, typically 3–9 per litter. This species is an essential predator, helping regulate populations of small animals in Florida ecosystems.

Brown Recluse Spider (Loxosceles reclusa)

The Brown Recluse Spider is a venomous arachnid known for its necrotic bite. It is relatively small, about 0.25–0.75 inches in body length, with a light to dark brown color and a characteristic violin-shaped marking on the cephalothorax. Despite its name, the spider prefers seclusion and avoids humans.

Brown Recluse Spiders are typically found in undisturbed indoor areas such as attics, closets, and storage rooms, but they can also inhabit outdoor debris, woodpiles, and sheds. They are nocturnal hunters, preying on insects and other small arthropods.

Their venom contains enzymes that destroy tissue, potentially leading to painful necrotic lesions. Most bites are minor, but severe reactions can occur, requiring medical intervention. The spiders bite defensively when trapped or pressed against the skin.

Reproduction occurs in warmer months, with females laying egg sacs containing 40–50 eggs. Brown Recluse Spiders help control pest insect populations in and around homes. Awareness and careful handling of areas where they live are the best precautions against bites.

Black Widow Spider (Latrodectus mactans)

The Black Widow Spider is one of Florida’s most well-known venomous spiders, easily identified by its glossy black body and the distinctive red hourglass marking on the underside of its abdomen. Adult females measure about 0.5 inches in body length, while males are smaller and less venomous.

Black Widows prefer dark, undisturbed areas such as woodpiles, sheds, garages, and crawl spaces. Outdoors, they may inhabit dense vegetation or under rocks. They build irregular, tangled webs close to the ground, waiting for prey to become ensnared.

Their venom is neurotoxic and can cause muscle pain, cramping, nausea, and severe discomfort, though fatalities are rare with proper medical treatment. Bites usually occur when the spider is disturbed or pressed against the skin. Immediate medical attention is recommended, especially for children or elderly individuals.

Black Widows feed on insects and other arthropods, capturing them in their sticky webs. Females lay several egg sacs each year, each containing hundreds of eggs. Despite their fearsome reputation, Black Widows play an important role in controlling insect populations in Florida ecosystems.

Lionfish (Pterois volitans)

Lionfish are invasive marine fish introduced to Florida waters from the Indo-Pacific. They are easily recognized by their striking red, white, and brown striped bodies and long, fan-like venomous spines. Adults can grow up to 15 inches in length, and their spines deliver venom capable of extreme pain.

Lionfish inhabit coral reefs, mangroves, and rocky coastal areas, often hiding in crevices during the day. They are ambush predators, remaining motionless before striking unsuspecting prey. Their presence in Florida waters poses a threat to native fish populations due to their aggressive hunting habits.

The venom of Lionfish is delivered through dorsal, pelvic, and anal spines. Stings cause intense pain, swelling, and in some cases, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. While rarely fatal to humans, stings require immediate first aid, including immersion in hot water and medical attention.

Lionfish feed primarily on small fish and invertebrates, drastically affecting reef ecosystems. They reproduce year-round, with females releasing thousands of eggs in gelatinous masses. Efforts to control their population include targeted removal and public awareness campaigns.

Stonefish (Synanceia spp.)

Stonefish are among the most venomous fish in the world and can be found in shallow coastal waters of southern Florida. They are well-camouflaged, resembling rocks or coral, which makes them easy to step on accidentally. Adults typically measure 12–15 inches in length.

Stonefish inhabit sandy or muddy bottoms near reefs and mangroves, blending perfectly with their surroundings. They remain motionless, waiting for prey to come close. Their camouflage makes human encounters particularly dangerous for swimmers and fishermen.

Stonefish venom is delivered through 13 sharp dorsal spines and can cause excruciating pain, swelling, tissue death, and even cardiovascular shock if untreated. Prompt medical attention is critical, often involving antivenom administration in severe cases. Hot water immersion can help reduce pain temporarily.

These fish feed on small fish and crustaceans, striking quickly with their large mouths. Stonefish reproduce sexually, with females releasing eggs that develop in open water. Despite their danger, they are an important predator in coastal ecosystems.

Portuguese Man O’ War (Physalia physalis)

The Portuguese Man O’ War is a marine cnidarian, often mistaken for a jellyfish, found floating in Florida’s warm coastal waters. It has a distinctive blue, purple, or pink gas-filled float and long trailing tentacles that can extend up to 30 feet.

This species drifts on the surface of the ocean, carried by winds and currents. The tentacles contain thousands of specialized cells called nematocysts, which deliver venom to capture prey. Contact with these tentacles can occur accidentally while swimming or boating.

The venom can cause severe pain, welts, and in rare cases, systemic reactions such as difficulty breathing, fever, and shock. Immediate medical attention is advised, and rinsing the affected area with saltwater and removing tentacles carefully are recommended first-aid measures.

Portuguese Man O’ War feeds primarily on small fish and plankton, paralyzing them with venom before consumption. They reproduce through a complex colonial system with both male and female polyps, allowing them to proliferate effectively in warm waters.

Florida Bark Scorpion (Centruroides hentzi)

The Florida Bark Scorpion is the state’s most common scorpion, measuring 2–3 inches in length. It is light brown to tan with a slender tail ending in a venomous stinger. Though not usually fatal to humans, its sting can be extremely painful and cause localized swelling.

This scorpion prefers warm, humid environments such as woodpiles, leaf litter, and the bark of trees. They are nocturnal hunters, emerging at night to feed on insects and other small arthropods. Their small size and camouflage make them difficult to spot during the day.

The venom contains neurotoxins that cause sharp pain, numbness, and tingling. Severe reactions are rare but can occur in children, the elderly, or allergic individuals. Medical treatment is recommended if symptoms worsen or persist.

Florida Bark Scorpions reproduce during the warmer months, with females giving live birth to 20–40 young. Despite their painful sting, they play a beneficial role in controlling insect populations and maintaining ecological balance in their habitats.

Centipedes (Scolopendra spp.)

Florida is home to several centipede species, including the giant red-headed centipede, which can reach lengths of 6–8 inches. These arthropods are elongated, segmented, and have numerous legs, each segment bearing a pair of legs. Their first pair of legs is modified into venomous forcipules used to capture prey.

Centipedes inhabit leaf litter, soil, mulch, and under rocks or logs. They prefer warm, humid environments and are most active at night. Human encounters are usually accidental, such as stepping on or handling them.

Their venom causes intense localized pain, swelling, and redness. Although centipede venom is rarely life-threatening, it can trigger allergic reactions in some individuals. First aid includes cleaning the wound, applying ice, and taking pain relief if necessary.

Centipedes feed on insects, spiders, and other small invertebrates, using their venomous forcipules to immobilize prey. They play an important role in controlling insect populations and maintaining ecological balance in Florida’s forests and gardens.

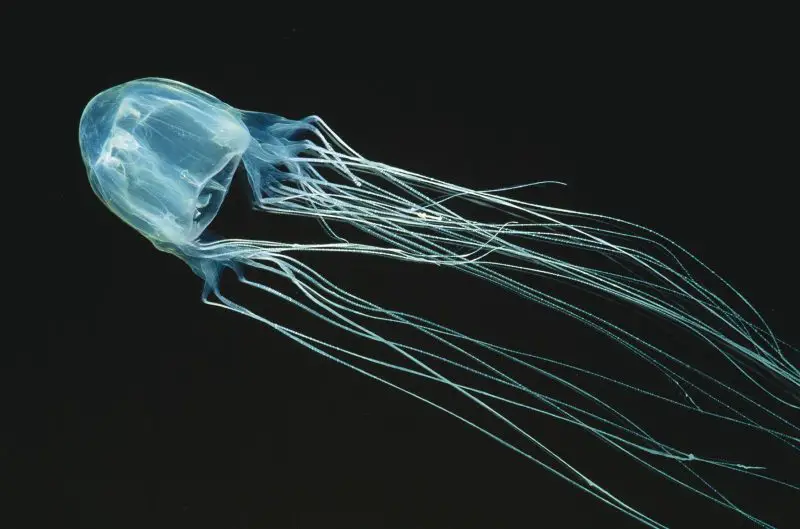

Box Jellyfish (Cubozoa)

Box jellyfish are highly venomous marine creatures occasionally found in Florida’s coastal waters, especially during warmer months. They have a cube-shaped bell and long, trailing tentacles that can reach several feet in length. Their translucent appearance makes them difficult to spot in the water.

These jellyfish drift in shallow waters, feeding on small fish and plankton. Their tentacles contain thousands of nematocysts capable of injecting venom instantly upon contact. Swimmers are most at risk when stung accidentally.

The venom is potent and can cause intense pain, welts, muscle cramps, nausea, and, in severe cases, cardiovascular or respiratory distress. Prompt medical attention is critical, and first aid often includes rinsing the area with vinegar to neutralize remaining stingers.

Box jellyfish reproduce sexually, releasing eggs and sperm into the water. Despite their danger to humans, they are predators in marine ecosystems, helping regulate fish and plankton populations. Awareness and caution are key when swimming in areas where box jellyfish may appear.

Best Times and Places to Observe

Florida is home to a diverse range of poisonous and venomous wildlife, but spotting them safely requires understanding their seasonal patterns and habitats. Many snakes, spiders, and marine animals are more active during warmer months. For example, rattlesnakes like the Eastern Diamondback and Pygmy Rattlesnake are most frequently observed during spring and summer when they emerge to hunt and mate. Similarly, box jellyfish and Portuguese Man O’ War are more common in coastal waters from late spring through early fall.

When it comes to locations, each species has preferred environments. Snakes such as the Southern Copperhead and coral snake are often found in wooded areas, scrublands, and near leaf litter, while scorpions and spiders favor sheltered spaces like logs, woodpiles, or the crevices of tree bark. Marine species like lionfish and stonefish inhabit reefs, mangroves, and shallow coastal waters, whereas jellyfish drift near the surface, carried by currents. Observing wildlife in these locations during daylight or low-tide periods increases the chances of seeing them safely from a distance.

Safety should always be your priority. Keep a respectful distance and avoid reaching into hiding spots or touching unknown animals. Use binoculars or zoom lenses for photography, and consider wearing gloves and long clothing if exploring areas with high spider or scorpion activity. Avoid stepping on logs, rocks, or coral blindly, and always tread carefully in shallow waters where marine species may be camouflaged.

Photographing or identifying these animals safely requires patience and proper equipment. Use long lenses to avoid disturbing the animal, and never attempt to handle venomous species. Observing their behavior, coloration, and environment can provide identification clues without risking a bite or sting. Documenting your sightings in journals or photos can help you learn patterns over time, making future excursions safer and more educational.

Safety Tips for Avoiding Poisonous Animals in Florida

Protecting yourself starts with appropriate clothing and footwear. When hiking or exploring forests, wear sturdy boots, long pants, and socks tucked in to minimize skin exposure. Gloves are useful when handling debris, firewood, or rocks. On the beach or in shallow waters, avoid walking barefoot, as marine species like stonefish and lionfish can be hidden under sand or coral.

Be cautious around unknown plants, water areas, and potential hiding spots. Poisonous or venomous creatures often use natural camouflage to blend into their surroundings. Avoid stepping into tall grass, piles of leaves, or under logs without checking first. In water, watch for floating jellyfish or camouflaged fish, and never touch unfamiliar creatures.

First aid basics are crucial for bites and stings. Clean the affected area with soap and water, immobilize the limb if necessary, and apply a cold pack to reduce swelling. Keep the victim calm and monitor for severe reactions such as difficulty breathing, dizziness, or spreading swelling. For marine stings, vinegar can help neutralize toxins from jellyfish or Portuguese Man O’ War tentacles, and hot water immersion can alleviate pain from lionfish or stonefish stings.

Seek immediate medical attention if symptoms worsen, if the bite is from a venomous snake or spider, or if the person is a child, elderly, or allergic. Prompt treatment, including antivenom for snake or severe marine envenomations, can prevent serious complications and even save lives.

FAQs About Poisonous Wild Animals in Florida

Which poisonous animal in Florida is most dangerous?

The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake is often considered the most dangerous venomous animal in Florida due to its size, potent hemotoxic venom, and defensive behavior. However, fatalities are rare with timely medical care. Marine species like box jellyfish and stonefish also pose significant risks in coastal areas.

Can coral snake bites be fatal?

Yes, Eastern Coral Snake bites can be fatal if left untreated. Their neurotoxic venom can cause respiratory failure. Fortunately, bites are rare because coral snakes are reclusive, and prompt administration of antivenom and medical care dramatically improves outcomes.

Are lionfish a threat to swimmers or just divers?

Lionfish can sting anyone who accidentally steps on or touches their venomous spines, so both swimmers and divers should exercise caution. While stings are rarely fatal, they cause intense pain, swelling, and sometimes nausea, requiring first aid and medical attention.

How can I treat a sting from Portuguese Man O’ War?

Rinse the affected area with saltwater to remove tentacles, never use freshwater. Carefully remove any remaining tentacles with gloves or tweezers. Immerse the sting in hot water (not scalding) to reduce pain and seek medical attention if symptoms are severe or systemic.

Are centipedes deadly to humans?

No, centipede stings are not deadly to humans. They inject venom that causes intense pain, redness, and swelling. Severe allergic reactions are rare, but anyone experiencing prolonged symptoms should consult a doctor.

Conclusion

Recognizing venomous and poisonous wildlife in Florida is crucial for both safety and education. While encounters can be dangerous, most species are shy and avoid humans if left undisturbed. Observing these animals responsibly allows you to appreciate their beauty and understand their ecological roles.

Respecting wildlife, maintaining a safe distance, and following safety guidelines not only protect you but also preserve the natural balance of Florida’s ecosystems. From snakes controlling rodent populations to marine predators regulating fish and invertebrates, these species are integral to the state’s diverse and thriving wildlife.